Notes From The Archives – Pro Racing

July 12, 2018Pro Racing

Words by: Gary Horstkorta

Tracy Bird was an early member of the SCCA and began his racing career in 1953 in what else but an MG TD. Over the next thirteen years he raced primarily on the west coast in a variety of cars including Mercedes Benz, Porsche 356, Fairthorpe Electron, Porsche 550, Maserati and finally a Cooper Monaco.

Bird was inducted into the SCCA National Hall of Fame in 2005. The following was written for his induction ceremony:

After early involvement as a racer and race organizer, Tracy Bird entered the national SCCA limelight as a member of the Contest Board and Activities Board. He was elected to the original SCCA Board of Governors which we now call Directors, and he served as its second Chairman of the board. He was appointed SCCA’s representative to ACCUS, and later served as SCCA Executive Director or President.

Bird’s leadership saw the club through the internal struggle over whether SCCA would be a gentlemen’s sports club or an international sanctioning body. He is my personal hero for the role he played at the forefront of the battle over control of road racing in America in the sixties. No single person has played a bigger role in shaping this club into what it is today. The following article was written by Bird, then the SCCA Executive Director, it appeared in the December 1970 issue of SportsCar. It is an excellent summary of the decisions that allowed amateur racers to enter professional events without fear of losing their licenses as once was the case. Note that one of the Board of Governors who participated in these discussions was our own Jim Lowe, an SFR Hall of Fame inductee in 2015.

One of the problems facing the first Board of Govenors at its initial meeting in New Yourk on November 2, 1958, was what to do about a dozen or more drivers whose licenses had been suspended for competing in a professional road race at Riverside in early October of that year.

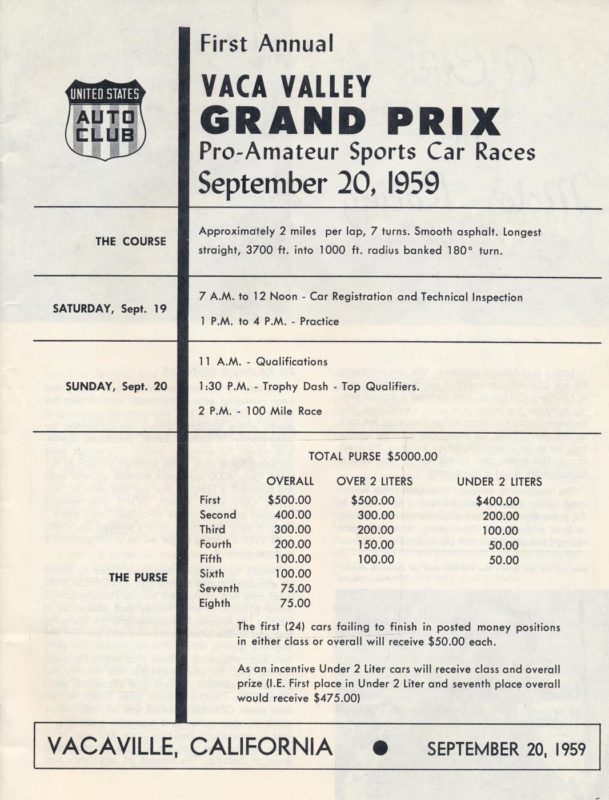

SCCA had been fighting professionalism in road racing since the time, seven years earlier, when the Contest Board of the AAA, together with a few radical SCCA members, had tried a take-over of the club’s racing program. In 1958 the United States Auto Club, successor to the AAA as the sanctioning organization for Indy and the “Championship Trail” of circle-track racing, announced the formation of a Road Racing Division.

At the time, SCCA’s policies were based upon strict amateurism and drivers had to make the choice of racing SCCA for glory, or giving up their licenses to race elsewhere for cash. USAC, then as now, exerted a pretty rigid control over their licensed drivers and had the idea that they could put on a traveling circus-like show, using a nucleus of Indy-name drivers as the headliners to attract spectators and filling in the grids with local sporty-car drivers who were willing to bolt the amateur ranks for the lure of cash.

It was a pretty good idea. Enough of our drivers were attracted by the promise of loot and the opportunity to try their skills against those of the Indy drivers to give USAC their traditional 33 car fields, and enough of our workers volunteered to help the usual four paid USAC officials to afford a race organization for events.

But a couple of developments changed USAC’s rosy picture. First, there weren’t all that many good sports racing cars available for the Indy drivers, who also had to face the problem of turning right. And, at least partially because of this, the sporty-car drivers consistently put the USAC stars to shame when they met on road courses.

This development in turn created problems for SCCA since, even though the prize money wasn’t all that great after paying the USAC entry and license fees required, the attraction of beating Rodger Ward or some other famous driver was enough to entice our drivers to these events. At the time, USAC didn’t have enough road racing events to satisfy the normal sports car driver’s urge to race and couldn’t lure a wholesale defection of SCCA drivers, but the danger was apparent and we were faced with the hassle of constant suspensions after their events.

Of the first Board of Governors, 11 of the 13 were active or retired drivers and five of us had professional racing experience either as a driver or car owner, so the board was well-equipped to be able to see both sides of the situation. After many hours of deliberation, the board arrived at a stop-gap solution to the problem. It lifted the driver suspensions then in effect and passed a new policy of allowing SCCA drivers to compete in events of other organizations, professional or not, if such events were approved by our Contest Board and provided that drivers maintained their amateur status.

From today’s point of view, such a policy may seem schizophrenic, but it eased the existing problem and gave us some breathing time to analyze the potential of professional road racing. But it also created new problems for both USAC and SCCA.

The problem for USAC was that, while their few professional road races were an artistic and financial success, they were being dominated by SCCA drivers as time went on. And, since they lacked an experienced and knowledgeable corps of officials and workers to conduct their events, SCCA race organizations began to take over the entire job of running them.

This situation reached its most ludicrous point at Laguna Seca, where the two or three USAC blazers of their officials were lost among the wire wheel emblazoned jackets of the San Francisco Region members around the Start-Finish line. It also created an understandable regional viewpoint that USAC and their dwindling handful of Indy stars weren’t needed for a successful Monterey Grand Prix.

Because the SCCA still reserved the right of approval of these events for the participation of its members in them, it in effect held an axe over the USAC road racing program. By the fall of 1960, during my term as chairman of the Board of Governors, this must have been evident to them, because Tom Binford, the USAC president, wrote me to ask for a meeting with our board for the purpose of discussing a proposal for cooperation between the two organizations.

By this time it was quite apparent that professional road racing was a fact of life, whether we liked it or not, and SCCA would either have to cooperate in some fashion, or put up a fight. Already, some regions involved in USAC events were threatening to run their own pro races and were holding them in line with the threat of charter revocation.

At my invitation, Tom Binford and Henry Banks appeared at the Board of Governors fall meeting to present their proposal. The discussion before they came into the meeting revealed strong feelings on the part of many governors against USAC, first for venturing into the field of road racing and secondly for expecting SCCA to cooperate in any way to make the venture a success.

From the prevalent attitude of the board, it was obvious that strict control of the session was necessary, so ground rules were laid whereby the USAC people were to speak their piece without interruption, then any questions were to be in writing only and passed to the chairman to read to them. As it happened, this procedure was all that kept the meeting from degenerating into a shouting match, since many of the questions were quite pointed.

In substance, the proposal was that, since the few professional road races they had conducted had been successful and public interest was growing, USAC and SCCA should enter into an arrangement whereby USAC handled the promotional and financial aspects of these races, including setting up and distributing prize money, and SCCA ran the races for a fee. They frankly admitted that they did not have the organization necessary to conduct road racing and that the proposed arrangement would obviate their going to the trouble of setting one up.

In the ensuing private meeting, the Board of Governors was unanimous in their rejection of the proposal. However, the reasons expressed were quite varied and generally demonstrated an awareness that we could not simply turn our backs on the growing professionalism in our sport.

The following year saw more pressures upon the governors from regions, drivers, and the owners of permanent road courses. USAC’s professional road races were gaining in national prominence and most of their success was due to the helping hands of our drivers, officials and workers.

Although staunch amateurism was still the ideal in many regions and the minds of a few governors, the head of steam was up and the blow-off came in mid-summer of ’61, when a special meeting of the board was called for July 29th in Chicago. At this meeting a new racing policy was proposed by Hendrix Ten Eyck, a freshman governor who had made a dispassionate study of the professional racing problem in SCCA.

Jack Hinkle was chairman then and, although a vigorous foe of professionalism, wanted to give the entire problem a fair shake. He convened the meeting into a Committee of the Whole in order to ensure that adequate discussion of the Ten Eyck proposal would develop without the danger of debate being closed by some ram-rod motion and vote.

With governors like Bill Martinez, Jim Kimberley, and Jim Lowe in the group, you can believe that the debate was hot and heavy. It lasted all day Saturday and into the dinner party at Jim Kimberley’s apartment that evening. The issues boiled down to the fact that professional road racing was here to stay and SCCA could either control it or take a back seat in the sport by continuing to ignore it.

Sunday morning we reconvened as the board and quickly and unanimously passed a series of motions that lifted the previous restrictions against members participation in professional races and gave SCCA the green light to proceed toward the control of professional road racing. All that remained was the problem of gaining that control.

When the word got out, it received the enthusiastic support of the majority of the regions and membership, particularly those with experience in the pro races. Other regions not having that experience set about planning professional races for future scheduling.

With the help of members of regions close to existing pro races, we then set about convincing the promoters of those races that, since they already involved SCCA drivers and race organizations, the only logical step was to request SCCA sanction and SCCA application for the necessary FIA listing. We also conceived our own national series of professional races, the United States Road Racing Championship, to commence in 1963. These moves were so successful that, by 1963, SCCA sanctioned and conducted every professional road race in the country and USAC’s Road Racing Division was out of business.

Over the past seven years, the list of professional road races sanctioned and conducted by SCCA has grown in numbers, stature, and public recognition. The Club’s entry into professional racing was not without internal struggle, but we banded together effectively against the outside. Let’s hope we can have the same support from our regions and drivers in the impending struggle with a new outside road racing division.